The Substance of “The Substance”

It has been quite some time since a film has left such a profound impact on me that I felt compelled to immediately run, not walk, to Letterboxd to scribble down my racing ethical, philosophical, and theatrical thoughts. Typically found are some of my cheekier commentaries or run-on sentence rants. However, once my thoughts on The Substance began to flow, I simply could not stop. What began as a few nonsensical notes, quickly morphed into a stream of consciousness… which evolved into a nonsensical rant… and ultimately, a full-fledged disquisition on both the filmmaking techniques and it’s deeply resonating thematic commentary.

The Substance: A Satirical Body Horror Experience

French writer and director Coralie Fargeat’s latest film, The Substance, is a masterful blend of body horror, dark comedy, and social commentary. Crafted with exceptional direction and ludicrous practical effects, it is a cinematic gut-punch that brilliantly utilizes the horror genre to explore society's obsession with industry beauty standards and women’s youth. Both absurd and grotesque, it offers a biting critique of misogyny while delivering an unsettling cinematic experience with imagery homages to the 80’s creature-features and horror classics like Carrie, The Shining, The Fly, and The Thing. In a genre largely recognized for its’ formulaic, predictable jump-scares, The Substance emerges as a powerful social commentary that demands attention and introspection from its audience. With committed performances from the elite cast, and dedicated storytelling skills and techniques from the crew, this film cements itself as one of the most compelling horror films of the year, perhaps the decade.

Filmmaking Techniques

Fargeat’s signature cinematic style enhances the film’s horror through captivating cinematography, atmospheric music, and a meticulous sound design, making The Substance a viscerally immersive experience. The camera work plays a crucial role in evoking discomfort, particularly through lingering shots on unsettling imagery. For fans of body horror classics like Alien, Leviathan, The Fly, and The Thing, The Substance delivers an unrelenting barrage of surrealistic imagery. It is easily the most revolting film of the year, pushing the boundaries of practical effects and audience tolerance. However, the film’s horror is not just skin-deep; its true terror lies in its brutally honest portrayal of how women are discarded once they reach a certain age. The story follows an aging woman who is deemed irrelevant by her predatory male employers, only to be replaced by a younger counterpart. The film’s message is far from subtle, but its exaggerated tone makes the bluntness of its commentary feel entirely appropriate. Ultimately a film that revels in its absurdity while delivering a sharp critique of beauty standards, with a razor-sharp focus on the entertainment industry’s misogyny in particular. With stellar performances, stylish direction, and some of the most nauseatingly effective practical effects in recent memory, Fargeat’s latest work is an unforgettable and uniquely disturbing experience. It is a testament to the power of horror as a vehicle for social commentary and a must-watch for those who can stomach its grotesque brilliance.

Production Design

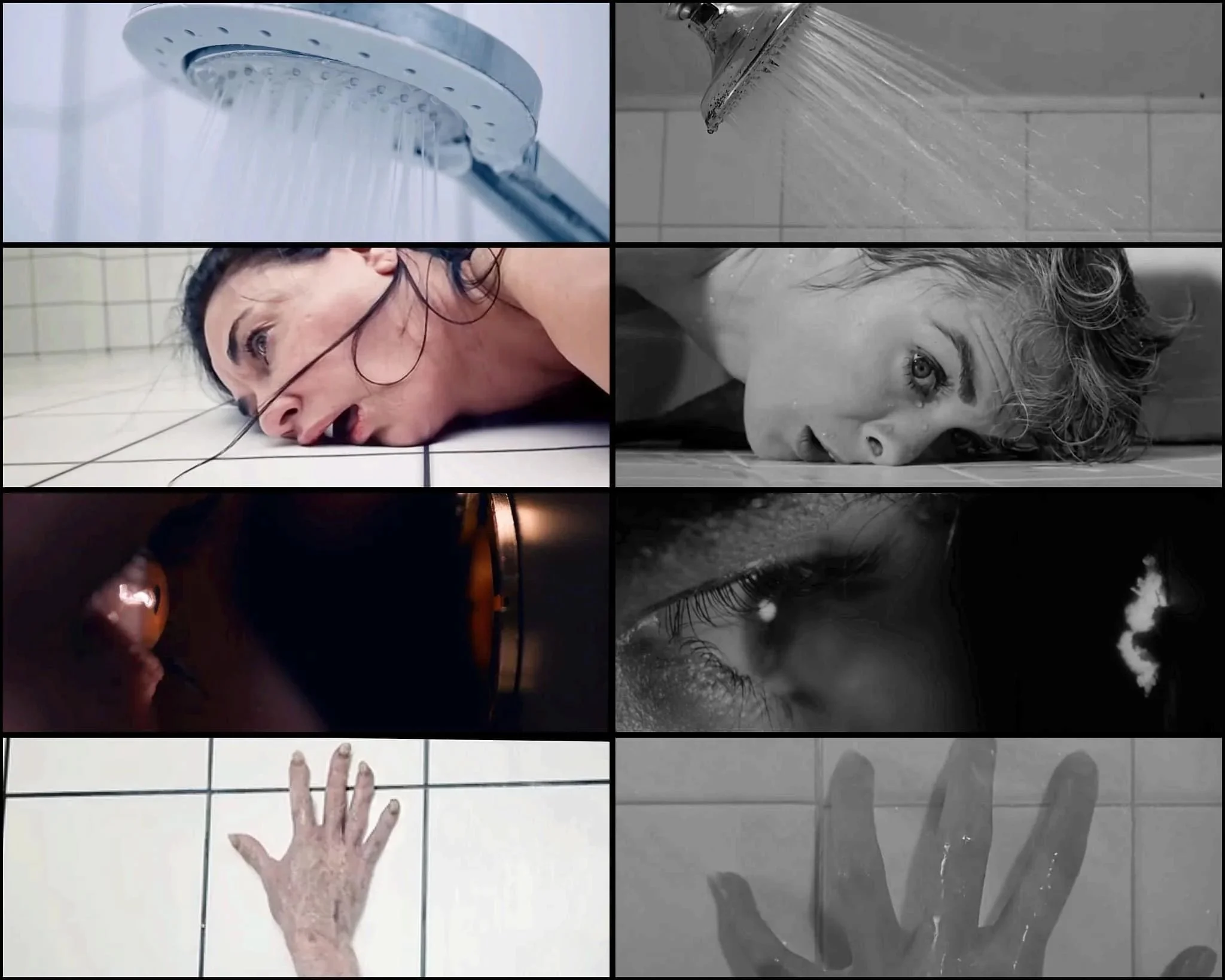

At first glance, certain production elements felt incredibly Kubrick: the set design, the transitional editing, the camera work. However, viewing the film in its’ entirety, cinephiles may notice many more of the classic 80’s horror nods the nostalgic writer/director brilliantly and artfully left behind for the audience’s discovery. Some of the more obvious inspirations coming from Kubrick’s The Shining in the set design of the studio’s hallway (pre- and post-blood soaking), the studio bathroom, and the laboratory-esque black and white tiled, clinical bathroom with pops of vibrant colors. I personally had never recognized Kubrick’s emphasis on jarring color until associating so much of it in these references. This film honestly re-awakened the long dormant cinephile in me. While examining the movie on strictly a plot basis alone is enough for a full post-mortem film autopsy, the references left for an exciting easter egg hunt for cinephiles and horror genre fans alike. It felt like an entirely separate layer worth dissecting, in an already heavy cinematic experience. Other references to the 80’s classic horror films include Carrie, Videodrome, and The Fly.

Another notable and intentional set theme was its very clear reference to the 80’s. In fact, if it weren’t for the usage of mobile phones, we might assume it was indeed taking place in 80’s. The career choice of Elisabeth being a very Jane Fonda-esque step aerobics instructor. The use of select color schemes, the intensity of saturation, as well as the costuming. It very intentionally replicated the feeling of the 80’s movie. This has been interpreted in many ways, and the interpretation is one that can be left to the audience’s discretion—whether it was purely a stylistic choice, or meant to replicate that feeling of the 80’s where so many of Fargeat’s references came from, or a nod to the era in which Elisabeth was likely at her “peak.”

Lighting and Color Palette

The film utilizes a "pink noir" aesthetic, blending elements of classic film noir with a modern, vibrant color scheme. The color grading of the film further enhances its themes. Elisabeth’s scenes are typically muted and desaturated, blues and teals aligning with the somber reality of her character’s experience. In contrast, Sue’s sequences are saturated with vivid colors, particularly bright pinks and reds, which contribute to the artificial and hyper-feminine aesthetic. The use of color is not only visually striking but also deeply symbolic. The film also utilizes rust colors like orange, yellow, and red, contrasting them with blues, teals, and greys to create a distinct visual dichotomy. This careful use of color and perspective adds depth to the storytelling, making the audience feel as though they are witnessing an unsettling experiment unfold.

Perhaps even more emphatically, lighting is not just a technical element, but a storytelling device carrying a crucial role in shaping the mood, tone, and audience perception of the environment and its subjects. Through its use of light and shadow, the film creates atmosphere, guides audience focus and reinforces the transformation of characters. As the protagonist undergoes changes (both mentally and physically) the lighting around them shifts accordingly. The transition from natural, warm lighting to more artificial, cold, or extreme lighting is an example between the character of Elisabeth and Sue. The strategic use of light and shadow is perhaps the least subtle use of lighting. Sue is always bathed in bright studio-lighting that eliminates imperfections, creating a hyper-idealized version of beauty. In contrast, Elisabeth’s lighting is far more shadowed and indirect, casting shadows that accentuate every wrinkle, skin fold, or body nuance. A great example of this would be the moody shot of Elisabeth in the backless dress at the cocktail bar. Whereas Sue is more often seen in studio bounce lighting, that offers no opportunities for unflattering shadows to form. She is presented as that advertised “dolphin smooth” we are all too familiar with as women.

One of the most immediate effects of lighting in The Substance is the establishment of atmosphere. The film employs a mix of high-contrast lighting, moody color palettes, and shifting light sources to reflect the emotional states of the characters. In scenes of suspense, dim lighting and deep shadows create an unsettling tone, heightening tension and uncertainty. Conversely, bright, sterile lighting may be used to contrast the horror elements, emphasizing moments of stark reality or scientific detachment.

The film also utilizes vivid primary colors— red, yellow, and blue—in striking color contrasts to reinforce themes of identity and transformation as well as invoking discomfort within the audience. The opening scene’s yellow yolk set against a blue background is a prime example of this technique. The contrast is mirrored later in Elisabeth’s wardrobe—her yellow coat often juxtaposed against cooler-toned surroundings or her blue leotard in the red and white bathroom creates another visually arresting contrast. Another fun theory of audiences, is that Elisabeth is consistently dressed in Primary colors, as the Matrix, while Sue is seen in predominently secondary colors, as The Other. This theory does not hold true, as we do see Elisabeth in Teals and Sue in Yellows on occasion, but a fun theory nonetheless!

Cinematography

Now for another exciting angle, let’s talk cinematography! Some of the more recognizable camerawork strategies were the utilization of macro lenses for intense detail close-ups. As well as wide-angle lenses, while still uncomfortably close, also capture the surrounding environment while distorting the subject’s appearance. The long lens typically utilized for capturing protagonist/s in her natural state, from both eye level and Birdseye view angles as well, creating that distancing between the character and the audience. So, let’s dive into the why’s of these techniques.

The Substance employs innovative camera work and visual strategies to explore themes of identity, beauty, and societal expectations. Cinematographer Benjamin Kracun's approach is instrumental in crafting the film's distinctive aesthetic, which oscillates between stark realism and stylized abstraction. One of the most striking camera techniques in The Substance is the use of macro lenses. These lenses allow for extreme close-ups that highlight intricate details, such as the texture of Elisabeth’s skin. These shots serve a dual purpose: they expose the natural aging process, making Elisabeth’s wrinkles and lines visible in a way that reinforces Hollywood’s obsession with youth, while also being used to incite discomfort. For example, the same lens is employed for nauseating close-ups of Harvey, played by Dennis Quaid, emphasizing the yellowing of his teeth and the effects of smoking. This stark contrast in the way the characters are presented visually reinforces the film’s critique of the entertainment industry’s double standards regarding aging and physical appearance. Additionally, macro shots and wide-angle lenses are strategically employed to distort features and intensify the unsettling atmosphere. Initially, Elisabeth is captured through a long lens, presenting her in a natural and flattering manner, with camera movements that are static and traditional: left to right, up and down— mimicking a comfortable and familiar perspective. However, as the film progresses and Elisabeth’s youth is stolen, she is increasingly filmed using wide-angle lenses, which distort her features and make her appearance seem grotesque. Additionally, the use of wide-angle lenses and zoomed-in shots creates a dizzying effect, mirroring the protagonist's disorientation and transformation. In contrast, Sue’s sequences are shot in a highly stylized and commercialized manner, reminiscent of old advertisements. The camera movements become dynamic, emphasizing her body in a way that mirrors the industry’s objectification of women. Every frame of Sue is meticulously crafted to present her as a product, aligning with the narrative’s critique of Hollywood’s treatment of female bodies, because at the end of the day, Sue is seen as a product to the industry in which they seek to make profit from.

One of the film’s most striking choices is its use of nudity and hyper-sexualized imagery. Unlike traditional horror films where the female body is exploited for the male gaze, The Substance presents these moments through a deeply unsettling lens. Margaret Qualley’s character performs provocative, sensual movements that, in another context, would be intended to arouse the audience. However, the way these scenes are framed forces the viewer to confront the discomfort and guilt associated with society’s objectification of women. It’s a scathing critique of how media and advertising capitalize on sexualized imagery while simultaneously dehumanizing the individuals within it. Diving into a specific example, you see a particular female attribute a number of times— The female breast is presented to you in full gaze in several scenarios: One is on Elisabeth as examines her body in a critical manner in front of the bathroom mirror. While perhaps shocking to the audience, it is by no means sexual and is indeed a clinical view of a human body without the use of certain context. The camera is kept static, and at a comfortable angle and distance. Another is when Sue is dancing for the camera. This is viewed with some context. Thumping music, and dynamic shots caressing her body in an extremely graphic manner. The third context of a human breast is one literally being convulsed up by Monstro Elisasue, what essentially feels like Coralie mustering up her final gift to Hollywood with a “Here, this is what you want!” While we are indeed still looking at a human female breast, the sexual context has been completely stripped away. At this point it becomes a very ridiculous and absurd combination. There is nothing sexual about it, it is utterly revolting and disturbing. At the end of the day, that is all it is, it is just a physical attribute, just a part of the body. But it is the context that Hollywood and the outside world place upon it that makes it something sexual.

Another unique camera perspectives employed to emphasize key themes were the birdseye view shots, or top-down angles, frequently used to create the sensation of observing human trials—reinforcing the film’s exploration of exploitation. Also creating the space in which the audience too feels as though we are observing the human trials of The Substance.

Overall, the camera work in The Substance is a masterclass in visual storytelling. Each cinematographic choice serves a greater purpose, forcing the audience to confront the industry’s harsh realities while immersing them in a world that is as visually compelling as it is unsettling.

Sound Design

Sound design plays a more crucial role in horror films in particular, shaping the audience’s emotional and physiological responses while keeping them in an unsettled state. The Substance, utilization of sound goes beyond traditional horror tropes, creating an experience that is deeply visceral and disturbing. By employing a meticulously crafted soundtrack, stomach-churning bodily noises, and manipulations of auditory perception, it immerses its audience in agonizing discomfort.

One of the most effective ways it employs sound is by means of its eerie soundtrack. Rather than relying solely on musical cues to build suspense, the film uses sound in a more primal way, triggering unease and revulsion. Dissonant tones and abrupt shifts in sound create a jarring effect that mirrors the revolting transformations on screen. The soundtrack does not provide relief; instead, it amplifies the anxiety, leaving the audience perpetually on edge. By integrating pulsating, irregular sounds that seem to mimic bodily functions, The Substance establishes an auditory landscape that feels as organic and repulsive as its visual horrors. However, the heart of The Substance’s audio mastery is its ability to create discomfort through hyper-realistic body horror sound effects. The film makes extensive use of squelching, cracking, and stretching noises, intensifying the uncomfortable nature of the physical transformations taking place. These sounds are exaggerated to such an extent that they become almost unbearable, making the audience feel every break, rupture, and contortion. The crunch of bones shifting out of place, the slosh of fluid moving unnaturally within the body, and the tearing of flesh contribute to a deeply unsettling experience. By focusing on these auditory details, the film forces viewers to engage with the horror on a sensory level, evoking a visceral reaction that goes beyond mere visual discomfort.

Another masterful technique The Substance employs is its manipulation of auditory perception. The film strategically muffles sounds at crucial moments, simulating the disorientation of characters undergoing changes. This muffled hearing effect disorients the audience, making them feel as though they are experiencing the horror firsthand. Moments of near silence punctuated by sudden, jarring noises heighten tension and contribute to an overall feeling of unease.

Moreover, the film does not shy away from using irritating, high-pitched frequencies that resonate uncomfortably with the human ear. These sounds serve a dual purpose: they mirror the agony of bodily transformation while also making the audience physically uncomfortable. This auditory assault aligns perfectly with the film’s themes of body horror. It does not merely accompany the visuals, but enhances them, ensuring that the horror is not only seen, but deeply heard and felt.

Costuming

Costuming in film is a crucial tool for storytelling, character development, and thematic reinforcement. Emmanuelle Youchnovski, the film's costume designer, effectively utilizes wardrobe choices to emphasize identity, transformation, and visual contrast. The strategic color choices and styles serve as a critical lens through which the film's commentary underscore the narrative's critique of beauty standards and reflect character development.

One of the most striking examples being the persistent presence of the yellow coat. This singular costume choice serves as a visual anchor in distinguishing characters, reinforcing thematic elements, and creating powerful visual contrasts. This costume choice in particular feels incredibly intentional; the bright, almost aggressive hue of the coat makes it impossible to ignore. Yellow is a color that demands attention, and its presence in the film ensures that Elisabeth remains a focal point. Not to mention the incongruity of the heavy and warm appearance of the coat being a stark contrast to the sunlit, warm atmosphere of Los Angeles. However the most obvious utilization is likely a direct reference to the film’s opening scene, which prominently features a yellow yolk against a blue background. This imagery establishes a visual motif that recurs throughout the film, creating continuity for The Matrix.

A key aspect of the costuming is how it differentiates between Elisabeth (the Matrix), and Sue (the Other). The Matrix is the only character who consistently wears the same outfit—the yellow coat—cementing her identity in the narrative. On the other hand, The Other quickly discards the coat and adopts new clothing, the first being the cutout leotard she saw in a storefront. This marks a clear departure from Elisabeth’s identity, as The Other embraces transformational reinvention. This distinction between the characters is further emphasized through Sue’s evolving wardrobe. Unlike Elisabeth, Sue's outfits and colors continually change, further isolating Elisabeth and establishing a clear differentiation between these characters that are meant to be “One.”

The film's exploration of transformation extends to its practical effects and costume design. Margaret Qualley, portraying Sue, underwent physical transformation and prosthetic alterations to embody the character. This included wearing prosthetic breasts to achieve an '80s-inspired aesthetic, reflecting the impossible beauty ideal of having a lean body but with curves in the “right places”— further emphasizing the film's commentary on the lengths individuals go to conform to societal standards. As well as the over-the-top, likely claustrophobia-inducing, full body prosthetics to bring Monstro Elisasue to fruition. And let’s not forget to give Demi and the prosthtics department their flowers on her gradual, but intense transfromation as well!

Another memorable costuming choice is the image of Sue running home in her blue sparkly dress—evoking a familiar and striking parallel to Cinderella racing against the clock before her magical transformation dissolves into reality. Sue's blue sparkly dress is reminiscent of Cinderella’s iconic ball gown, a garment that symbolizes wish fulfillment, beauty, and an external transformation that temporarily elevates her status. In both cases, the dress is more than just attire—it is a representation of an illusion, a fabricated identity that is unsustainable without an external force. Cinderella's magic fades at midnight, and Sue's artificial state enhanced by the Substance, begins to disintegrate with the death of Elisabeth. The ticking clock in both narratives create suspense, but more importantly, it reflects a universal anxiety—the fear of losing something fleetingly beautiful and returning to an undesirable state. Through this parallel, the stories prompt reflection on the nature of self-worth and the illusions we chase. Cinderella ultimately finds happiness not through magic but through self-acceptance and recognition of her own value. Sue, on the other hand, may serve as a cautionary figure—her desperate sprint for another dose suggests an ongoing struggle with dependence and the peril of seeking self-worth through temporary fixes.

Thematic Elements

Now let us dive into the thematic elements of the analysis.

External Validation

Elisabeth’s life is filled with awards, accolades, and recognition, all of which serve as external markers of success. For Elisabeth, she has reached the pinnacle of financial, physical, and societal achievement. She is beautiful, accomplished, and seemingly has it all. Yet, despite her undeniable success, her life feels utterly empty. The tragedy of Elisabeth’s character lies in the fact that her self-worth was never intrinsic; it was derived entirely from the validation of others. Every aspect of her existence—her beauty, her achievements, and her recognition—was merely a reflection of external approval. The moment these external sources began to fade, so did her sense of self. Elisabeth’s story highlights the dangers of a life driven by external validation. Despite being an accomplished and objectively beautiful woman, she remains deeply insecure. Her relentless pursuit of approval pushes her beyond the point of no return. Instead of reaching a stage in life where she can take pride in her accomplishments, she perceives it as an end—a place of shame rather than fulfillment. The validation she thrived on has dried up, leaving her feeling discarded and irrelevant. This highlights the fragile nature of external validation; once it disappears, so does one’s perceived worth.

The corridors in the studio serve as a powerful visual for Elisabeth’s journey. As she walks through them, we see years of accolades and recognition, charting her progression from early success to the pinnacle of her career. In contrast, when we switch to Sue, the hallway is nearly empty, save for a single image. This stark contrast symbolizes Sue’s life is just beginning, while Elisabeth’s has reached its perceived conclusion. The second corridor we see Elisabeth navigate through is the alley Elisabeth must take to acquire the substance— a journey through a dodgy and foreboding space. Her willingness to traverse such an ominous place for The Substance reflects her desperation to reclaim her lost validation. Throughout the story, Elisabeth ignores glaring red flags. When first presented with the flash drive, she initially discards it, sensing the absurdity of it. However, upon realizing the void left by her lost external validation, she retrieves it and embarks on her journey of self-destruction. The red flags continue when she calls the supposed medical provider, and they fail to ask for any of her medical details or even her name. A rational person would question such a suspicious procedure, but Elisabeth, blinded by desperation, ignores the warning signs. She arrives at the dodgy location, where she must physically contort her body to crawl through a dark, grimy corridor. Even the lockers, which only bear two numbers, serve as an eerie recognition that she is one of only 2 test subjects, (the other we can only assume later on to be the man that slipped her the flash drive in the beginning). Every step of the way, she disregards caution in pursuit of validation, illustrating the lengths she will go to regain what she has lost.

Elisabeth’s descent into self-hatred and self-harm is further illustrated in her dream sequences. In one dream, she envisions Sue’s organs falling out, waking in horror and immediately checking Sue’s body. In another dream, it is Sue experiencing the negative side effects of the self-sabotage that Elisabeth is currently engaging in via a chicken wing. In both nightmares, their greatest fear is the loss of Sue’s perfect body. The worst-case scenario for both women is the erosion of their external validation, reinforcing the idea that their worth is intrinsically tied to their appearance and recognition.

Despite everything Elisabeth endures, she does not learn from her mistakes. Sue’s storyline serves as a mirror to Elisabeth’s past, yet Elisabeth does nothing differently. She returns to the same company, the same job, and surrounds herself with the same superficial influences. She fails to recognize that this path will inevitably lead to the same cycle of being discarded. Elisabeth Sparkle had everything—awards, accolades, fans—but all of it was temporary and superficial. At the end of the day, she is left utterly alone, devoid of fulfillment, family, or genuine relationships. And yet, she willingly returns to the cycle, seeking love and validation through recognition, popularity, and fame. In the end, Elisabeth’s tragedy is not just her downfall—it is a cautionary tale of the perils of living solely for external validation.

The Depiction of Men

The depiction of men in The Substance is nothing short of a boorish caricature, a deliberate and exaggerated reflection meant to hold up a mirror to those in power. The film’s portrayal of figures like Harvey (played by Dennis Quaid) leans into the absurd, presenting him as a cartoonishly evil, morally bankrupt executive who reduces women to commodities. It is clear that Coralie Fargeat crafted these portrayals with the explicit intention of making men in these positions confront their own actions—though, whether they actually will is another matter entirely.

Harvey’s character unmistakably echoes Harvey Weinstein, a comparison that is impossible to ignore. From his physicality to his mannerisms, he embodies the Hollywood executive archetype that Weinstein so infamously defined: a man who wields power over women’s bodies and careers with unchecked dominance. He does not see Sue as a person, but as a product, something to be molded, marketed, and ultimately disposed of. The way he speaks about her and to her is devoid of any real human connection, reinforcing the idea that to men like him, women are mere tools for their success.

What makes The Substance so riveting is how unsubtle it all is—there is no delicate hand here, no nuanced approach to gender dynamics. It is loud, brash, and wildly entertaining in its forcefulness. The film refuses to let these issues be ignored, instead shoving them back into the audience’s face in a way that feels both cathartic and damning. The moment Harvey calls Sue his “greatest creation,” with the audience knowing full well the monster about to emerge onstage, is a particularly satisfying example of this approach. The sheer irony and poetic justice of it all make it one of the film’s standout moments.

The absurdity and exaggerated nature of the executives in The Substance bears a strong resemblance to the way corporate masculinity was portrayed in Barbie. Both films take the idea of corporate power and strip away any attempt at humanization, revealing these figures as hyperbolic distortions of themselves. In Barbie, the executives were bumbling, clueless, and completely out of touch; in The Substance, they are insidious, self-serving, and terrifying in their ability to manipulate and control.

Another striking contrast in the film is how Elisabeth’s struggles with consumption and self-image are hidden away in private, while Harvey’s indulgences are on full public display. His gluttony—whether it be for food, power, or control—is shameless, a stark contrast to Elisabeth, who must suppress her desires and maintain an illusion of perfection or seek it in the privacy and isolation of her home.

All of this is wrapped in an undeniably camp aesthetic. The film does not shy away from excess, instead embracing it as a stylistic and thematic choice. This heightened, almost theatrical quality makes the crudeness of the men even more pronounced, pushing them further into the realm of parody while still maintaining a deeply unsettling undercurrent of reality. As I sit here writing this, I can’t help but note the ironic microcosm playing out to my left—a man who has fully claimed this shared bench as his own, his body language invasive, pratically brushing my shoulder with his fingertips, legs angled and strewn in my direction, his attention split between the waitress he is loudly flirting with and the woman I assume to be his wife. His presence, his unconscious assertion of space and dominance, is a reminder that the kind of men depicted in The Substance are not exaggerated fantasy—they are real, they are pervasive, and they exist in both the grandest and smallest of spaces.

Symbolism

The Substance employs a variety of symbolic elements to explore themes of identity, self-destruction, and the allure of fame. These symbols contribute to the film’s exaggerated, campy aesthetic while also underscoring its darker undertones.

One of the film’s most visually arresting symbols is the recurring image of the Hollywood Walk of Fame star. This symbol, while somewhat clichéd, plays a crucial role in conveying the film’s commentary on fame and self-worth. The fact that the protagonist’s name is Elisabeth Sparkle makes this symbolism even more on the nose. Initially, the obviousness of this imagery felt perhaps too heavy-handed, almost veering into parody. However, as the film embraced its campy and exaggerated style, the bluntness of this symbol became more fitting. The Hollywood Walk of Fame star represents both the dream and the delusion of stardom. It is an emblem of recognition and immortality, yet it is also something that thousands of forgotten names share, eroding into the sidewalk over time. This duality reinforces the film’s exploration of the fleeting and often hollow nature of fame.

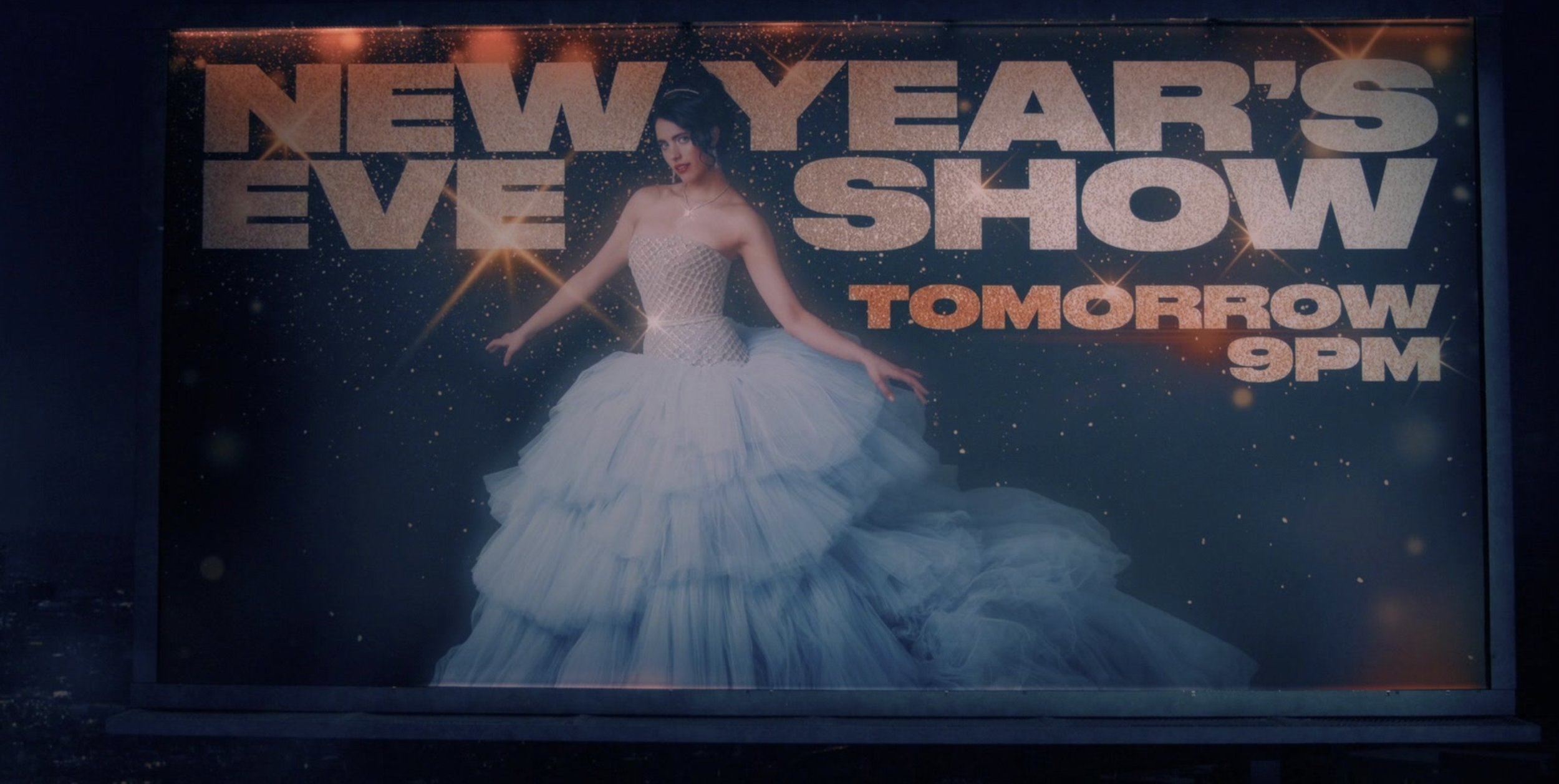

Another recurring symbol is the frequent attention towards the portrait of Elisabeth and the billboard of Sue. Each serve as powerful visual symbols that highlight the film's themes of identity, societal expectations, and the duality of self. The classical portrait of Elisabeth represents the idealized, respectable version of herself—the one she has worked hard to maintain in a world that values appearances over authenticity. It reflects a traditional, almost outdated notion of beauty and worth, reinforcing how she feels trapped by aging and irrelevance in the entertainment industry. In stark contrast, Sue’s massive, glossy billboard symbolizes the seductive yet dangerous allure of The Substance. It embodies youth, desirability, and the promise of reinvention—everything Elisabeth is being told she is losing. However, the artificial nature of billboards and advertisements hints at the illusion behind Sue’s existence, foreshadowing the darker consequences of trying to replace one's true self with an idealized version. Together, these images juxtapose the old and the new, reality and illusion, suggesting that the pursuit of perfection comes at a terrifying cost.

Mother-Daughter Relationship Concept

In The Substance, the mother-daughter relationship serves as a powerful metaphor for the ways in which motherhood both physically and emotionally consumes a woman. Through the lens of pregnancy, birth, and the inevitable toll they take, the film explores how giving life can feel like a process of personal depletion. The relationship between Elisabeth and Sue explores the complex dynamics of motherhood, wherein love and potentially resentment coexist— particularly as mothers may feel they have sacrificed their own youth, beauty, and vitality for their daughters.

One of the most striking ways The Substance portrays the mother-daughter bond is through the physical and biological costs of pregnancy. Motherhood is inherently parasitic; during pregnancy, the developing fetus extracts nutrients, calcium, and other vital elements from the mother's body, often leading to long-term changes in her health and appearance. This aspect of biological sacrifice reflects the broader theme of a mother's diminishing selfhood in the process of raising a child. The literal draining of nutrients becomes a metaphor for not only the physical, but the emotional and psychological toll of motherhood—something that can leave a woman feeling hollowed out and depleted.

The film also explores another common but often unspoken tension in mother-daughter relationships—mothers who resent their daughters for their youth and beauty. In some toxic relationships, mothers attempt to live vicariously through their daughters, using them as extensions of their own unfulfilled dreams. Alternatively, a mother may become embittered, seeing her daughter as a painful reminder of her own aging. This narcissistic dynamic can lead to competition rather than nurturing, with the mother undermining the daughter’s confidence to maintain control. In The Substance, this struggle is evident in Elisabeth’s need to assert her authority and dismiss Sue’s achievements. By doing so, she reclaims a sense of power that she feels was lost in the activation of The Substance. Elisabeth’s treatment of Sue reinforces this notion— She constantly mocks Sue, reminding herself that she “wouldn’t have anything if it weren’t for her.” This statement, while partially true in the biological sense, also highlights the resentment that can build in mother-daughter relationships. Instead of feeling pride in Sue’s independence or beauty, Elisabeth diminishes her “daughter,” emphasizing her own role in creating and sustaining her. This behavior suggests that Elisabeth views Sue’s success as something she is owed, rather than something Sue has earned in her own right. Ultimately, The Substance presents a chilling exploration of how motherhood can become a cycle of consumption, resentment, and self-hatred. Through Elisabeth’s toxic relationship with Sue, the film critiques the way society often expects mothers to sacrifice endlessly without acknowledgment of their loss.

In opposition, the relationship between Elisabeth and Sue in The Substance serves as a dark metaphor for the way daughters—consciously or unconsciously—can take advantage of a mother’s unconditional love and sacrifice. As the film progresses, Sue gradually takes over, thriving at Elisabeth’s expense. This dynamic mirrors the way mothers often pour their time, energy, and even physical well-being into their daughters, sometimes to the point of self-erasure. Elisabeth initially embraces Sue as a means of regaining power and relevance, just as mothers may find purpose in nurturing their daughters. However, Sue begins to consume Elisabeth—both figuratively and literally—reflecting how some daughters, even unintentionally, can exploit their mother’s sacrifices without fully grasping the cost. The film explores the fear of being discarded once one's usefulness fades, much like how some mothers may feel abandoned or replaced when their daughters grow up and no longer "need" them in the same way. Elisabeth’s unwavering commitment to Sue, even as she loses herself, mirrors the way mothers can neglect their own well-being for their children. This is particularly true in relationships where the daughter, intentionally or not, takes advantage of the mother’s instinct to give endlessly, sometimes leading to burnout, resentment, or even a loss of personal identity. Ultimately, The Substance amplifies this real-life dynamic into a horror-driven allegory, showing the extreme consequences of self-sacrifice when love and devotion become a one-way transaction.

Despite her resentment, Elisabeth ultimately gives her life for Sue, demonstrating the paradox of motherhood: even when there is bitterness, the instinct to protect one’s child overrides everything else. This act of self-sacrifice reflects the way motherhood is an all-consuming role, one that demands everything from a woman, whether she wants to give it or not. Even when faced with the possibility of losing her, she does the one thing mothers have done for their children for generations—she gives everything, even at the cost of her own survival.

That Ending…

The explosive finale of The Substance is an unapologetic, grotesque spectacle—an overt, visceral rejection of the entertainment industry’s treatment of women. It is not subtle, nor does it attempt to be. Instead, it is a direct, loud, blood-soaked condemnation— throwing its themes directly into the faces of the audience.

At its core, the climax of the film is a manifestation of self-destruction. When Sue kills Elisabeth, believing she is eliminating the worst parts of herself, she is, in reality, killing her entire being. The moment she destroys her perceived flaws, her life immediately crumbles. In a final desperate grasp at reclaiming her manufactured ideal, she reaches for another dose of the activator. The monstrous horror that unfolds is not an external entity but a creature of Sue and Elisabeth’s own making—a direct result of the suffocating pressures of the industry. This is a beast born from self-loathing, industry pressures, and the internalized misogyny that demands eternal youth and perfection. The absurdity of the finale ensures there is no room for misinterpretation. The film is confronting the audience with the monster they, too, have had a hand in creating. It forces the viewer to reckon with the blood-soaked consequences of an industry that preys on women’s insecurities, a monstrosity that they are complicit in fostering. This is not a film that allows for passive consumption. The violence, the gore, and the sheer audacity of the finale are deliberate—there is no subtlety, and that is the point. The blood splattering across the screen is not just gore for the sake of shock; it is a direct, furious metaphor for the sacrifices women have made at the hands of this industry. Every drop of blood is a message, an accusation, a demand to face the ugly reality that has been constructed around beauty and worth.

The brilliance of The Substance lies in its thematic depth, particularly in the portrayal of Elisabeth’s compulsion to keep taking the substance despite its increasingly horrifying consequences. Her actions can be understood through the lens of self-hatred and self-harm. She does not love herself as she has aged, nor does she see any worth in who she has become. In her mind, Sue is the only part of her that deserves love, validation, and existence—because that is all the world has ever validated for her. Her pursuit of Sue, even at the cost of her own destruction, is emblematic of the way women are conditioned to chase a beauty standard even when it is actively harming them.

The film also makes it clear that no one is innocent. The industry, the audiences, the culture at large—all have blood on their hands. They have all contributed to the creation of this monster, to the endless cycle of validation and erasure that women in Hollywood endure. The casting of Demi Moore in this role is nothing short of masterful. Moore, a woman who has lived through the exact pressures the film critiques, brings an authenticity that makes the message even more searing. She is not just playing Elisabeth—she is, in many ways, embodying the lived experience of countless women in the industry.

Perhaps one of the most profoundly resonant moments is the scene of Elisabeth preparing for her date night. This is a moment of quiet devastation, one that feels deeply personal and universal to many women. It captures the relentless comparison to unattainable beauty standards—not just to others, but to a younger version of oneself. It is a scene that painfully encapsulates the way self-perception can be distorted to the point of complete alienation. Demi Moore is objectively stunning, not just “for her age” but in every sense of the word. Yet, Elisabeth cannot see that. She only sees Sue, the unattainable ideal, and in contrast, herself as an unappealing reality. This is visualized in the warped reflection in the doorknob—a perfect metaphor for the way self-image becomes twisted and unrecognizable under the weight of comparison. It is an honest, brutal moment that speaks to an experience so many women share. The more you look, the more flaws you see, the more you become detached from reality—trapped in an endless pursuit of a version of yourself that can never be regained. I watched this at such an interesting time, as I have just gone through a huge shift in makeup routine, because my face physically cannot wear makeup the way it used to. My under eyes are hollowing, my forehead wrinkles are settling, my crow’s feet are deepening, my cheeks are falling— and I am only 29 freaking years old. Wearing makeup like I used to just doesn’t work for me anymore, I have had to make a change. While yesterday I found myself lifting and prodding and smoothing and stretching in order to get my face to resemble what it did at a more youthful age— today, I feel completely nauseated at the thought of analyzing my face in the mirror. That director did her work—at least on me. And while I may feel this way for the next day, or week, or month, (or hopefully as long as a year), I know society’s commentary and pointed pursuit of preying on insecurities to make the big bucks, will once again reclaim me as prey. But what Coralie achieved with what many may feel was overkill or glorification of gore and perversion, was the entire point— to deeply, deeply, deeply unsettle and you in a confrontational manner. Unfortunately, oftentimes that is where drastic change and introspection happen. While this movie isn’t going to demolish the aesthetics industry, and Hollywood is certainly going to be the last to change, I think this was something that was and could be very powerful to audiences. Hopefully reaching the 50-year-olds that have gone too far with fillers, the 30-year-olds manipulated into preventative Botox, and save some of our youth from an expensive and self-critical journey. Movies can be such a cool, interesting way to put things into perspective. And this one handled the toxic cycle of the beauty industry very well.

Demi Moore herself has spoken candidly about her own struggles with self-image, making her performance all the more poignant. Her words about looking in the mirror—sometimes seeing beauty, sometimes tearing herself apart, but ultimately trying to make peace with what is—mirror the very themes the film explores. It is a battle every woman fights, a truth the film refuses to sugarcoat. The Substance is not just a horror film. It is an indictment, a furious, blood-drenched scream against the way women are commodified, discarded, and driven to self-destruction in pursuit of an impossible ideal. It does not ask for permission to be seen or understood—it demands it. It is confrontational, uncomfortable, and utterly unforgettable. And that is precisely what makes it brilliant.

The Takeaway

The resurgence of high-brow horror in recent years has given rise to films like Get Out, Hereditary, and The Babadook, which prove that horror is more than just gore and fear—it is a storytelling tool capable of delivering powerful social critiques. While themes of misogyny, ageism, and self-worth have been explored through dramas, biopics, and documentaries, horror provides a uniquely immersive and visceral experience. The horror in The Substance is not just about the nauseating physical transformations, but about the psychological horror of societal expectations. Women chasing youth is not a new narrative—it’s a tale as old as time, yet we are still. f*cking. telling it. Rather than retelling the story of another heartbroken woman aging out of her profession, or being replaced by an unfaithful husband with a younger, newer model, Coralie Fargeat chooses to take the more aggressive route. As opposed to metaphorically shouting it from the rooftops with films like Judy, First Wives Club, Gia, and Tootsie, The Substance feels like a literal vomit-inducing medication being force fed down your throat. It forces audiences to confront these concerning realities in a deeply uncomfortable way. The body horror, exaggerated to an almost unbearable degree, mirrors the real-world pain and suffering individuals willingly endure to adhere to beauty standards.

A Reflection of Society’s Role in Perpetuating Beauty Ideals

Additionally, the film does not just blame the patriarchy or media; it acknowledges that women themselves are complicit in this cycle. The horror of watching needles penetrate skin, fluids being drained and reinserted, bodies being stitched up and reshaped, is made all the more disturbing by the realization that these are not far-off horrors. Breast augmentation, Facelifts, Liposuction, BBL’s, Botox, and Fillers are all normalized aspects of modern beauty culture that are being bought into and re-sold as “self-care” and “female empowerment.”

As a member of the audience, you watch this woman and easily say “I would never,” when most of us literally have. Your boob job, your rhinoplasty, your fillers, your Botox— you have voluntarily put your body through surgical procedures, pain, and damage for aesthetics, all under the risk of permanent, irreversible damage, and in some instances fatality. You watch this woman submit to this horrifying experience willingly and distance yourself. Obviously, The Substance doesn’t exist. Obviously, you would never split yourself in two. Obviously, you would not carry through with 99.9% of the things that this fictional character has chosen to. But this horror movie is only an exaggeration of real-life implications. We are all Demi Moore’s trying to become Sue’s with the resources that are currently available to us.

Both The Substance and the world of cosmetic enhancements operate on the premise of transformation. The film’s protagonist undergoes repeated injections to achieve a certain ideal, but with each shot, the consequences become increasingly dire. This reflects the real-life experience of individuals who turn to cosmetic enhancements and procedures, often believing that a simple modification can reverse time and restore a youthful glow. However, just as in the film, these interventions are not always without consequence. The pursuit of an unattainable standard of beauty can lead to an unrelenting cycle of treatments, each one promising a fleeting sense of satisfaction before the next dose is required. One of the most harrowing aspects of The Substance is the protagonist’s dependency on injections. This dependency serves as a metaphor for the real-world addiction to cosmetic procedures. Many individuals who start with minor enhancements find themselves returning for more, unable to stop as their perception of beauty becomes distorted. The normalization of injectables and cosmetic procedures in mainstream culture further fuels this cycle, making it harder to recognize when enhancement turns into normalcy and obsession.

The film resonates on a deeply personal level, particularly for women who have internalized these impossible standards. As the protagonist undergoes horrific transformations to maintain youth and desirability, she loses herself entirely. The tragedy is not just in her physical metamorphosis, but in her emotional and psychological unraveling. This aspect of the film speaks to the real-life consequences of these societal pressures—the anxiety, depression, and body dysmorphia that plague individuals who feel they must change themselves to be accepted and desired. This theme is particularly relevant in an era where young women are undergoing cosmetic procedures at increasingly younger ages. The normalization of these interventions, fueled by social media, influencer culture, and celebrity endorsements, creates an environment where the natural aging process is vilified.

The Substance highlights the irony that even when women conform to these standards, they are still ridiculed when their conformity turns into overdone distortions that society advocated for in the first place. This transformation of the protagonist into a monstrous entity through the use of The Substance directly parallels the real-world phenomenon of women resorting to extreme beauty procedures, only to be mocked and ostracized for their efforts. The tragic irony is that the very society that pressures women into unnatural self-modification is the same one that shames them when they go too far. The creation of Monstro Elisasue represents the inevitable conclusion of a culture obsessed with flawlessness. In The Substance, the protagonist, struggling to maintain relevance and desirability, turns to a revolutionary procedure that promises perfection. Yet rather than achieving the beauty that would grant her societal acceptance, she instead becomes a monstrous, exaggerated version of herself.. This mirrors the way women, particularly those in the public eye, increasingly resort to cosmetic enhancements such as Botox, Fillers, and plastic surgery to maintain their value in a world that equates beauty with worth. However, the moment their enhancements become too noticeable, they are ridiculed, shamed, and labeled as “unnatural,” or even “monstrous.” The same audience that demands perfection punishes women for striving toward it.

Hollywood and the entertainment industry have long dictated rigid beauty standards that pressure women to remain youthful and attractive at all costs. Older actresses frequently struggle to find roles, as the industry often prioritizes fresh, young faces over experience and talent. This double standard forces women into a paradox: they must either age naturally and risk professional irrelevance or modify their appearance and face societal rejection. This dynamic is evident in The Substance, where the protagonist initially believes she is taking control of her own image, only to lose herself entirely. The more she conforms to expectations, the more alien she becomes, both literally and figuratively.

This theme extends beyond Hollywood and into everyday life, where social media perpetuates unrealistic beauty ideals. The rise of face-altering apps, filters, and cosmetic procedures has created a culture where women are expected to maintain an ever-youthful, flawless appearance. Yet, when the modifications become too visible—when lips are too plump, cheekbones too sharp, or faces too immobile—society turns on these same women, branding them as “plastic” or “unnatural.” This cruel cycle mirrors the fate of Monstro Elisasue, who is no longer recognized as human despite merely striving to be what the world demanded her to be.

The true horror of The Substance is not in the horrifying transformation itself but in the inescapable reality it reflects. Women who chase societal approval through self-modification are ultimately dehumanized, whether through rejection, mockery, or outright vilification. This hypocrisy underscores the impossible position women are placed in. They are simultaneously expected to be perfect yet punished for attempting to achieve perfection. The monstrous form of Monstro Elisasue serves as a metaphor for the way society warps women’s self-image, pushing them to extremes and then condemning them for it.

***These images are meant only to point out the examples of society ridiculing women in the media

The Lasting Impact of The Substance

The Substance is not just another body horror film—it is an unflinching critique of a culture that prioritizes youth and beauty at the cost of individuality, self-worth, and identity. It is a film designed to make you uncomfortable, to burrow under your skin, and to linger long after the credits roll. While it will not dismantle the aesthetics industry or Hollywood overnight, its impact is undeniable. It forces its audience to reckon with their own complicity in this toxic cycle, and for some, it may be the first step toward change. Horror has always had the power to expose our deepest fears, and in The Substance, those fears are not just of unappealing transformations but of the reality we live in every day.

The imagery in The Substance serves as a powerful allegory for the cosmetic industry’s role in shaping contemporary beauty standards. Both the film and the industry expose the lengths to which people will go to alter their appearances, often at great personal cost. Whether through the body horror of the film or the more socially acceptable procedures in real life, the underlying message remains the same: the relentless pursuit of physical perfection can come with unforeseen consequences, forcing individuals to question whether the sacrifice is truly worth it. As society continues to evolve, it is essential to foster a culture that embraces natural beauty and self-acceptance rather than one that glorifies an unattainable and often harmful standard of perfection.

GLOSSARY

Bounce Lighting: a photography and cinematography technique where light is directed onto a surface (like a wall, ceiling, reflector, or fabric) to reflect and diffuse it before it reaches the subject. This method softens the light, reduces harsh shadows, and creates a more natural, even illumination.

Macro Lens: a type of camera lens designed for extreme close-up, allowing you to capture subjects with incredible detail. Unlike regular lenses, macro lenses have a high reproduction ratio, typically 1:1.

Wide Angle Lens: a type of camera lens that has a short focal length, allowing it to capture a broader field of view compared to standard or telephoto lenses. These lenses emphasize perspective distortion, and offer wide field of view.

Long Lens: a type of camera lens with a long focal length, allowing you to zoom in on distant subjects. These lenses compress perspective, making it ideal for isolating subjects.

Body horror is a subgenre of horror that depicts the physical or psychological transformation of the human body in a grotesque or disturbing way. Also known as biological horror, organic horror, or visceral horror. It focuses on the graphic and disturbing transformation, destruction, or degeneration of the human body. The body itself becomes the source of fear, anxiety, and disgust. Generally, they explore themes of disease, decay, deformity, mutation, parasitism, or mutilation. Typical body horror—teeth falling out, nails falling off, skin opening up, needles being used/inserted, prsthetic enhancements and mutilizations, etc.